Kitwe HC4 is an hour down a dirt road, off the main road from Ntungamo. It has a good range of buildings, staff accommodation even a fully equipped operating theatre. But with no medical officer and no anaesthetist the theatre has been unused since it was built 5 years ago. Even when there was a medical officer in post a couple of years ago they are often new graduates and don't have the confidence to keep up a surgical practice. With no electricity, no running water and not much to do in the evenings it's hard to keep doctors there for any length of time. The team seemed bright and capable and were really trying to provide a good service. It's hard to see how they can stay optimistic in the face of their difficulties though. They had 2 clinical officers, 4 midwives 4 nurses , 3 nurse aides and a bunch of support staff.

Ruhama HC2 is a tiny enterprise started by a Ugandan in his old family house. Again, a good team, poor facilities but big ideas. Unfortunately it is less than 2 miles from a government health centre and the two seem to be in competition rather than collaborating to improve health outcomes. Why the NGOs and missionary outfits don't ever get involved in running and improving existing services I really don't understand. The Ruhama enterprise was interesting in its efforts to generate income locally to help fund the service. The running costs of $750 pcm which provided a nurse, 2 nurse aides, a lab technician , a finance officer and support staff were met 1/3 from user fees for medicines, 1/3 from the parent NGO and 1/3 from a variety of local projects. These included eucalyptus plantations to provide firewood for sale, a stone quarry and beekeeping enterprise as well as a savings and credit scheme. Addressing income in impoverished rural areas is vital.

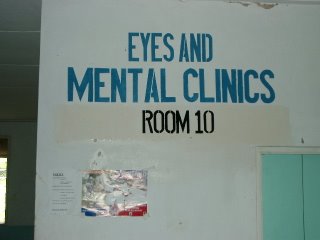

Our third visit of the day was to a HC2 run by brazilian nuns. The 20 minutes down a very rough dirt road gave no hint of the splendour of the unit. From being almost impassable the road gave out to a wrought iron gate in a crafted stone wall worthy of a Hollywood mansion. The concrete driveway flanked by luscious palms led through a manicured but productive garden to a gleamingly clean and welcoming purpose built health centre. The quietly spoken and determined nun seemed to have sorted the ideal arrangement. She had persuaded the district to give the centre its own budget which amounted to $500 pcm, which they spent on drugs. They then sell the drugs and lab tests at cost and use that money to pay staff wages (the nuns come free, they employ an additional nurse, a clerk, a lab technician and household support staff). Oh and she keeps a firm grip on all the keys so none of the stock disappears. The place was beautifully kept with plenty of welcoming posters and messages on the walls and doors. Enough to make you believe in God (or nuns at least).

Our final visit was to Rugarama HC4 in Kabale. Another splendid example of a mission based health unit, operating semi independently of the district but with a government budget. Well staffed and efficiently run, it was clearly delivering a high standard of care compared with the government hospital up the road, but again was charging user fees and there seemed to be no communication between the two units. The Ministry of Health Grant of $4000 pcm paid the wages of almost 80 staff. There were consultation fees inpatient charges and drugs and lab tests were charged at cost. Capital costs are met by donations usually from the International Lions organisation. They are hoping to start obstetric surgery soon and want to build a paediatric unit to allow the maternity unit to expand. They need to build more staff accommodation as providing accommodation is the only way to make their salaries competitive with government ones. Nurses are on $150 pcm, clinical officers on $250 and docs on $500.

We've done with visiting! It's been great to see so many examples of good and not so good practice, the challenges faced by overwhelmed government units and the contrast with better resourced private ones.

We're both left unsure about the whole business of user fees. Coming from the UK it goes against the grain to charge people at all for health care, let alone the really poor for treatment of diseases of poverty. But at least with the brazilian set up the charges were as low as they could be and were posted on the wall so people knew what was being charged for. We heard stories in government centres of parents having to go to a drug shop to buy the syringe and needle for their child to get the injection of antimalarials they desperately needed because the hospital had run out, and that isn't right either.